Understanding the Misleading Nature of Forecasting Trends

Written on

Chapter 1: The Dichotomy of Research Methods

In the fields of psychology, economics, sociology, and political science, researchers typically employ two primary methodologies: idiographic and nomothetic. The idiographic approach hones in on the unique characteristics of specific subjects or events, while the nomothetic approach seeks overarching patterns that elucidate broader societal trends, aiming to establish "laws" similar to those in the natural sciences.

Both methodologies offer valuable insights into culture and society, but complications arise when we try to draw sweeping conclusions from a set of isolated instances. Many biographies and historical narratives adopt an idiographic perspective, chronicling events with a level of detail akin to transcription. These accounts, focused on individual experiences in a specific context, may not universally apply. Nevertheless, some public intellectuals make sweeping nomothetic assertions in various media, claiming that events like the COVID-19 pandemic will lead to social upheaval and revolts due to shifts in power dynamics.

What justifies their assertions? They might reference the Black Death, which resulted in a significant loss of life and subsequent labor shortages, empowering peasants to demand better wages. In response, the government imposed new taxes, leading to widespread unrest, epitomized by the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381. Drawing parallels, they argue that COVID-19 could trigger similar outcomes.

While I don't dismiss these predictions outright, I highlight the troubling leap from idiographic observations to nomothetic claims without sufficient justification. This raises valid questions, especially since history has showcased numerous instances in economics where forecasts based on past data have failed miserably.

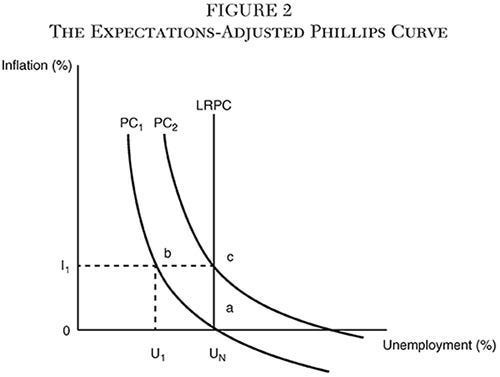

Consider a particularly infamous example: after a prolonged period of stable economic growth post-World War II, the United States faced a combination of high inflation and unemployment in the 1970s, dubbed “stagflation.” This situation was paradoxical because it contradicted the established Phillips curve, which suggested an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment. The unexpected nature of stagflation left even the most knowledgeable economists perplexed, resulting in policy missteps that diminished real income and living standards.

To maintain credibility, economists introduced the "long-run Phillips curve" model, which depicted a vertical line at the “natural rate of unemployment.” This model offered little clarity for policymakers and was essentially an attempt at damage control.

Chapter 2: The Evolution of Societal Structures

In earlier times, one might liken economic outcomes to a game of dice, where rolling a number determined the payout—thus limiting winnings to a predictable range. This scenario aligns with what Nassim Nicholas Taleb terms “Mediocristan,” a realm where extreme events are rare and outcomes are generally foreseeable.

In contrast, Taleb describes “Extremistan,” where a single significant occurrence can drastically alter the trajectory of events. In this environment, small advantages can lead to enormous rewards, exemplified by the "superstar effect." For instance, if two singers differ by just 1% in talent, the more skilled one might capture 99% of the market, while the other struggles to make ends meet. This phenomenon is evident across various fields, explaining why many creators face obscurity while a few achieve viral success.

In this competitive landscape, luck and timing often overshadow mere talent and hard work. For instance, one can achieve wealth through value creation, such as teaching or writing, but alternatives like gambling and speculative trading can yield similar outcomes, albeit at the expense of others. This illustrates that success can stem from diligent effort or fortunate circumstances.

Taleb articulates that "Mediocristan" subjects us to the collective norm, while "Extremistan" exposes us to the unpredictable and extraordinary. He argues that our current world increasingly mirrors Extremistan, where unforeseen events—such as viral sensations or technological disruptions—can have profound implications. Traditional businesses often find themselves trapped in Mediocristan, failing to adapt to transformative innovations. For instance, companies like Kodak and Blockbuster succumbed to bankruptcy after misjudging the impact of digital advancements.

Additionally, predictions from experts at the AGI-09 conference about achieving artificial general intelligence by 2050 have been accelerated dramatically due to advancements in large language models like GPT-4.

These instances underscore the complexities of making accurate long-term forecasts based on historical precedents or rigorous statistical analyses. Today's interconnected and technologically advanced society operates under systems and power dynamics that differ significantly from historical contexts. Although human behaviors may echo through time, the specific conditions can vary widely.

Returning to our COVID-19 discussion, one must ponder: What mechanisms trigger social unrest during a pandemic? Is it solely economic distress, or do psychological, political, and biological factors contribute? What conditions create the environment for unrest? It’s crucial to investigate instances where pandemics did not lead to instability to delineate the boundaries of our hypothesis.

These inquiries, though challenging, are invaluable. Rather than selecting narratives that reinforce our biases, we should approach these questions with the rigor of scientific inquiry. Before disseminating conclusions, we must ensure our theories can withstand empirical scrutiny. This approach will allow us to transcend the simplistic notion that "history repeats itself" and gain a deeper understanding of societal dynamics. Neglecting this process would be akin to a financial advisor disclaiming that their insights aren’t financial advice while recommending specific investments—an undesirable situation, to say the least.

Jonathan Barnes discusses the implications of synthetic polymer chemistry and how it shapes our understanding of future trends.

Stuart Candy explores the concept of designing our own futures in this TEDx talk, emphasizing the importance of foresight in uncertain times.

Thank you for engaging with my writing. Your attention in a world of diminishing focus means a lot. If my insights resonate with you, please consider following or leaving a comment. Your continued support is appreciated, whether you're a returning reader or discovering my work for the first time.