# Unraveling the Rich Tapestry of South Asian Ancestry

Written on

Chapter 1: The Journey of South Asian Ancestry

The narrative of humanity continues to evolve as innovative methods for extracting and analyzing ancient DNA enhance our grasp of our forebears. One undeniable takeaway is that our ancestors traveled extensively and were often driven by their desires.

In contrast to the wealth of European and Central Asian DNA findings, South Asian genetic evidence has been harder to come by. This scarcity is largely due to the region's warmer climate, which complicates preservation efforts compared to European samples. However, recent technological advancements have begun to illuminate the intricate formation of South Asian populations. In the past week, two groundbreaking studies were released, shedding light on the identity and origins of South Asians. These studies reinforce the significance of human mobility in shaping their ancestry. Before diving into the findings, let's briefly revisit the historical context.

Historically, the lack of DNA data has hindered our understanding of South Asian population formation, leading to theories primarily based on archaeological evidence. Early analyses of mitochondrial DNA indicated that the Indian population had deep indigenous roots. However, subsequent examinations of Y-chromosome data revealed connections to Western Eurasians, suggesting that male migrants entered the subcontinent while local women remained.

A comprehensive study conducted in 2018 delved into complete genomes, establishing two distinct groups in ancient India: Ancestral North Indians (ANI) and Ancestral South Indians (ASI). According to Harvard geneticist David Reich, these two groups exhibit differences comparable to those between modern Europeans and East Asians. This study scrutinized the genomes of 612 ancient individuals, incorporating samples from regions such as eastern Iran, Turan (encompassing parts of present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan), and South Asia. This data was juxtaposed with samples from 246 contemporary South Asian groups, further highlighting our intrinsic desire for movement and interaction.

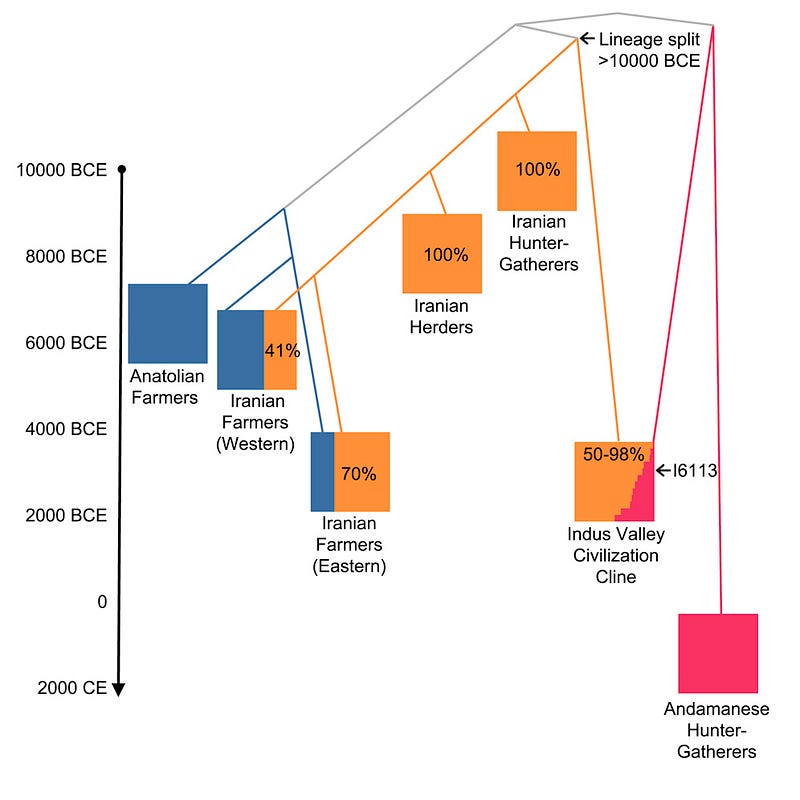

The findings reveal a rich narrative of migration and intermingling. Initially, South Asian hunter-gatherers, identified as Ancient Ancestral South Indians, are believed to have descended from the "out of Africa" migration approximately 50,000 years ago. Around 9,000 years ago, Iranian groups migrated into the subcontinent, intermingling with these hunter-gatherers and giving rise to the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), also known as the Harappan Civilization.

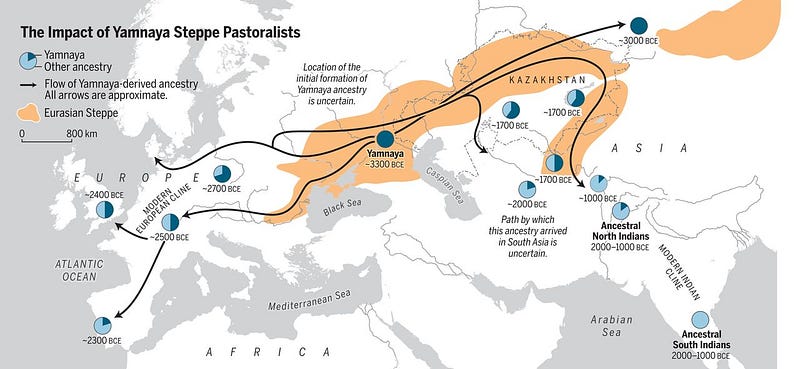

Subsequently, around 2,000 BCE, Indo-Iranian steppe pastoralists moved south, encountering the IVC population. This interaction led to some upheaval but primarily resulted in further mixing. The Indus Valley inhabitants migrated southward, blending with the hunter-gatherers to create the ASI group. In the northern regions, the pastoralists integrated with the remaining Indus Valley population, leading to the formation of the ANI group. Consequently, most contemporary South Asian populations are a product of ongoing mixing between these two ancestral groups.

Recent genetic analyses underscore that the Indus Valley people represent the most significant ancestral source for South Asia. This assertion is supported by a new study published in Cell, which examined the genome of a woman unearthed in Rakhigarhi, India, who lived between 2,800 and 2,300 BCE. Genetic and archaeological evidence suggests her affiliation with the IVC. Intriguingly, her genome reveals a blend of ancestries tied to ancient Iranians and Southeast Asian hunter-gatherers. Notably, the Iranian-related ancestry stems from hunter-gatherers predating agriculture by 2,000 years, indicating that agriculture in the Indian subcontinent likely developed independently and possibly in parallel with Iran.

The other recent study corroborates these findings, illustrating that while agriculture spread into Iran and Central Asia via migrations from Anatolia, the narrative in South Asia diverges significantly. The populations of the Indus Valley were genetically diverse, comprising early Iranian and local hunter-gatherers, and developed their agricultural practices independently. This study also highlights the genetic contributions of the Yamnaya steppe pastoralists to the ANI, alongside IVC populations, which likely facilitated the similarities between Indo-Iranian and Balto-Slavic languages.

Nonetheless, this story is far from complete. Certain groups in India display closer ties to East Asians, particularly those speaking Sino-Tibetan languages in northern mountainous regions. Additionally, various eastern and central tribal groups communicate in Austroasiatic languages linked to Cambodian and Vietnamese ancestry, likely descended from those who introduced rice farming to South Asia and Southeast Asia. The Indian subcontinent, therefore, emerges as a melting pot, a crossroads where agricultural practices from the Near East (wheat and barley) and China (rice) converged.

In summary, humanity is inherently a tapestry of diverse ancestries. The concept of "pure races" is devoid of meaning, as both South Asians and Europeans share complex, intertwined heritages. The resulting diversity in languages and cultures is a testament to this rich mixture, and it is this complexity that deserves celebration.

Chapter 2: Exploring South Asian Identity

In the video titled "WTF Is 'South Asia'? - YouTube," viewers are introduced to the geographical and cultural complexities that define South Asia. This exploration reveals how the region's rich history and diversity shape modern identities.

The second video, "What does being South Asian really mean to me? - YouTube," presents personal reflections on identity, highlighting the unique experiences and stories that contribute to the South Asian narrative.