Bivalent Vaccines: Protecting Children Even After Infection

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding the Pandemic's Evolution

It has been merely four years since we first identified the virus now known as the coronavirus, previously labeled nCOV-19. This earlier name was somewhat more fitting, as the "n" signified "novel," which ultimately led to widespread challenges.

Coronaviruses were not entirely unfamiliar; four strains had long circulated globally, causing the common cold. However, the 2019 coronavirus was new to our immune systems, presenting enough differences that our immune memory cells struggled to recognize it. Instead of mimicking a typical cold, it manifested in unprecedented ways, marking a significant chapter in the story of our immune responses.

The contrast between early 2020 and the present—characterized by ongoing but less severe infections—can largely be attributed to advancements in immune education. Some individuals gained immunity through infection, while others were vaccinated, and many experienced both.

When the first vaccines were rolled out in December 2020, there was still a substantial opportunity to bolster our immune defenses. At that time, approximately 20 million people in the U.S. had contracted the virus, with 350,000 fatalities; however, a vast number remained without any immunity—myself included.

The period from early 2020 to early 2021 was marked by efforts to educate our immune systems. As we transitioned to a post-vaccination era, new variants began to emerge. From one strain to multiple variants, our immune memory, which had been tailored to recognize specific versions of the virus, became less effective. Although these variants were not "novel" like the original strain, they were different enough to cause reinfection.

In a manner reminiscent of the flu virus, which frequently alters its appearance, we have now entered what can be described as the booster era. The current recommendation is to receive annual vaccinations, ideally tailored to the circulating variants.

However, uncertainty still lingers about the vaccination strategy, particularly concerning two specific groups: individuals previously infected and children, who generally face a lower risk of severe outcomes.

This week, new evidence emerged to clarify these issues. A notable study, published in JAMA, investigates the effectiveness of the bivalent vaccine—introduced in September 2022—in safeguarding children against COVID-19.

Chapter 2: Insights from Recent Studies

It's important to note that this study was not a randomized trial. Previous studies validating the mRNA vaccine platform were conducted before its authorization, but trials for the bivalent vaccine primarily focused on immune response rather than disease protection.

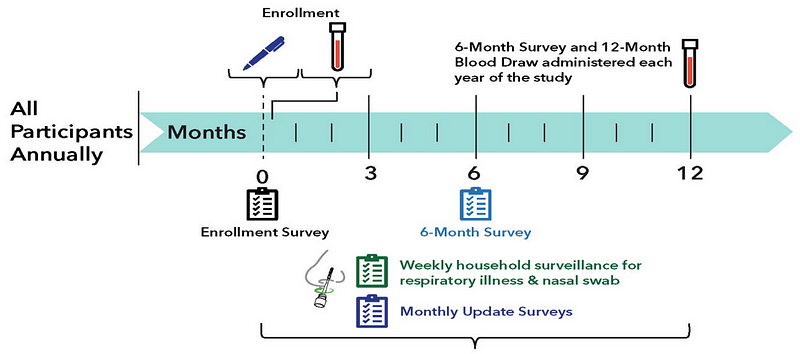

Nonetheless, employing robust observational methods and statistical analysis, researchers can glean insights into the effectiveness of the bivalent vaccine in children. This study integrates data from three prospective cohort studies, and crucially, children were tested for COVID-19 weekly, regardless of symptoms, recognizing the potential for asymptomatic transmission.

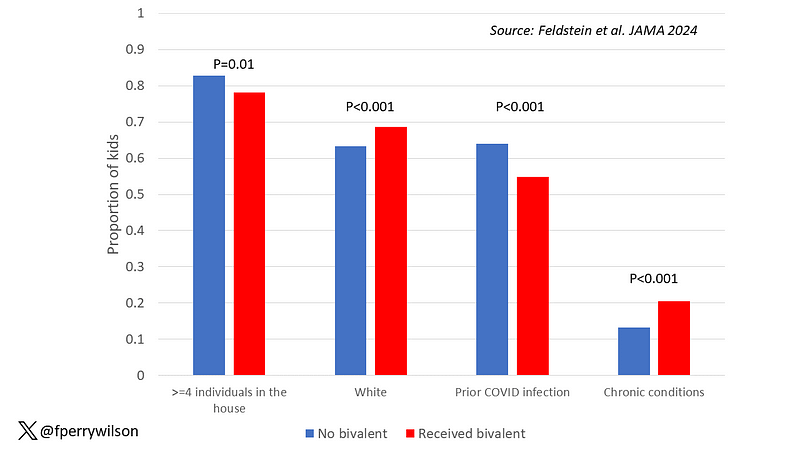

Key variables included whether children had received the bivalent vaccine, prior monovalent vaccination, and history of infection. The findings indicated that children who received the bivalent vaccine experienced a significantly lower infection rate.

After nearly a year of follow-up, about 15% of unvaccinated children contracted COVID-19, while only 5% of vaccinated children did. Symptomatic infections accounted for roughly half of all cases in both categories.

Adjusting for differing factors revealed that the bivalent vaccine demonstrated an efficacy rate of approximately 50% in this population. This indicates that the bivalent vaccine was effective—though not extraordinarily so.

Surprisingly, the vaccine's effectiveness remained consistent even among children who had previously contracted COVID-19. Among those not vaccinated, 10% were reinfected, compared to just 2.5% of those who received the bivalent vaccine. This suggests a synergistic effect between prior infection and vaccination.

While the data indicates that the bivalent vaccine reduced the risk of COVID-19 infection in children, it remains unclear how severe these infections were. Fortunately, none of the 426 documented infections resulted in hospitalization or death, and data regarding multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children was not provided, though its rarity suggests it was unlikely to occur.

In summary, there seems to be a prevailing narrative claiming that "vaccines don't work" or "vaccines are ineffective if you've already been infected," which is likely misguided. This study, along with others involving adults, demonstrates that vaccines do indeed work. If they can reduce infections—as shown here—they are also likely to decrease mortality rates, albeit the occurrence of death in children is fortunately rare, making the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one death significantly high.

Thus, the transition to an annual vaccination schedule akin to that for the flu may not merely be a case of habit—it could very well be a wise strategy.

The first video titled "Bivalent Vaccines Protected Kids, Even if They Had Been Infected Already" explores the recent findings of a study showing moderate protection from the bivalent booster in children.

The second video titled "The updated COVID vaccine: Who should get it and when it will be available with Sandra Fryhofer, MD" discusses recommendations on COVID-19 vaccination and updates on vaccine availability.