The Impact of Extended Summers on Polar Bears' Survival

Written on

Chapter 1: The Consequences of Climate Change

As the duration of summers increases, polar bears find themselves spending more time ashore, which drastically reduces their opportunities to hunt for their primary food source: ice seals.

Photo by Steve Payne on Unsplash

The interconnectedness of Earth's ecosystems is essential; they rely on various non-biotic factors like temperature and precipitation. Disruption of any of these elements can lead to widespread ecological collapse, impacting both wildlife and human economies.

While much attention is given to how climate change affects human populations, we must also consider its immediate effects on other species. One particularly striking example is the polar bear (Ursus maritimus).

Recent research led by Dr. Anthony M. Pagano and colleagues highlights how polar bears are responding to the rapidly changing climate in Manitoba, Canada. Between 1979 and 2015, the ice-free season in western Hudson Bay has expanded by three weeks due to rising temperatures.

At first glance, three additional weeks without ice might seem insignificant for polar bear survival. However, a closer examination of their ecological needs reveals severe consequences. The study notes that polar bears primarily gather energy during a short window in late spring and early summer when seals are birthing and nursing their pups. As climate change extends the ice-free periods in the Arctic, polar bears are compelled to move to land.

When forced onto land, polar bears often fast or resort to foraging for less nutrient-dense food. My research on mammal dentition during my doctoral studies drew my attention to the polar bear's specialized carnivorous teeth, which are notably sharper and more suited for hunting than those of other bear species like grizzlies or black bears.

3D scan of a Polar bear (Ursus maritimus) specimen from the National Museum of Natural History (USNM 275072). Image from Digimorph.org

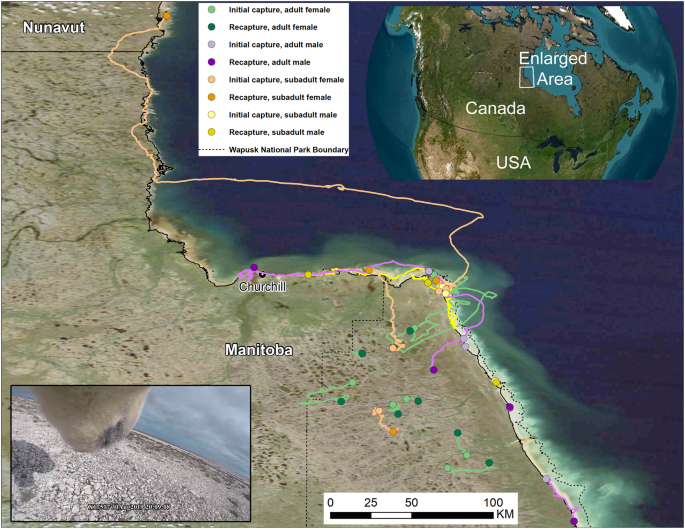

To assess how prolonged ice-free periods affect polar bear survival, the research team monitored the behavior and foraging patterns of 20 polar bears over 19-23 days from August to September (2019-2022). This group included a mix of adult females, adult males, and subadult bears, all fitted with GPS-enabled video camera collars to measure various metrics, including energy expenditure, dietary habits, and body composition.

Map of polar bear movements derived from GPS-enabled video camera collars, capturing the locations and movements of 20 polar bears near Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. The data provides insight into their activity and foraging strategies.

The findings surprised the researchers. Contrary to their expectations that polar bears would minimize activity to conserve energy, they observed a range of adaptation strategies. Some bears increased their activity levels to enhance their chances of finding food, while others conserved energy by remaining in smaller areas, exhibiting metabolic rates akin to those seen in hibernating bears.

Interestingly, the bears with lower initial weights, suggesting poorer health, were more likely to fast. In contrast, pregnant females with higher fat reserves showed reduced movement. As someone who has experienced pregnancy, I can empathize with their energy-saving strategies.

Another compelling observation was that some polar bears undertook long-distance swims (over 50 km) during this period. Equipped with video cameras, researchers noted that these bears occasionally encountered beluga carcasses during their swims but typically did not feed on them.

In this video, researchers discuss the findings of their study on polar bears and their ability to adapt to changing climates.

Despite varying strategies among the bears, overall body mass loss did not show significant differences based on activity levels. Notably, most bears favored the increased activity approach, which could have critical implications for the terrestrial ecosystems surrounding Hudson Bay.

Chapter 2: Changing Ecosystems and Polar Bear Adaptations

With the lengthening summers, polar bears, typically apex predators, will increasingly compete with other carnivores, such as grizzly bears and wolves, for food resources. This shift could disrupt local animal populations. For instance, snow geese, which used to nest in late spring when polar bears foraged on ice seals, have faced declining numbers as bears begin to consume their eggs earlier due to climate change.

Images showing polar bears foraging on land near Churchill, Manitoba, Canada, including an adult female consuming various food sources.

However, while polar bears may turn to alternative food sources, these options are not as nutritionally adequate as their traditional diet of ice seals. Approximately 70% of their diet while on ice consists of fat. In fact, only one bear managed to gain weight during the three-week study, having found a substantial land mammal to eat.

The study revealed that the most active polar bears experienced losses in both body fat and lean mass, which is atypical for hibernating species. The authors provide an extensive discussion on metabolic changes, which those interested in "ketosis" may find particularly enlightening.

The researchers concluded that further studies are necessary to fully grasp the adaptations polar bears may need to endure due to shifting climatic conditions. They noted that they did not examine body mass changes in lactating females, who experience significantly increased energy demands during this critical reproductive phase.

Dr. Andrew Derocher, a biology expert at the University of Alberta, commented on the findings, stating:

“This paper clearly shows that polar bears cannot adapt to the pace of change in the Arctic and that the bears are already using everything they have to stay alive.”

Photo by Hans-Jurgen Mager on Unsplash

The most concerning takeaway from this study is the potential for starvation among bears as summers lengthen, which could hinder their survival until the next breeding season for ice seals. A staggering 95% of the polar bears in the study lost body fat, underscoring that "none of the energetic strategies adopted by the studied individuals were beneficial for surviving the on-land period."

Historically, during interglacial periods with reduced ice cover, polar bears relied on large mammal carcasses that washed ashore to supplement their high-fat diet. However, dwindling whale populations have made these opportunities increasingly rare.

In conclusion, the study's authors assert that as summers grow longer, polar bears will face extended periods on land, significantly heightening their risk of starvation. While previous discussions have explored the broader implications of climate change, most models indicate a continued warming trend driven by human-induced carbon emissions. The cascading effects of climate change are extensive and will challenge all species, including our own.